History of Isselmere-Nieland

| History of the UKIN | ||

|---|---|---|

| Periods General Early Pre-History Bronze Age Iron Age Anglic migrations Norse migrations Joergenian dynasty House of Glaines Reformation | ||

| Nations Anguist Detmere Gudrof Isselmere Nieland | ||

The United Kingdom of Isselmere-Nieland (UKIN) is a moderately sized kingdom on the southern side on the modest island of Lethe, bordered on the northeast by the Ungforth Marshes separating the kingdom from the Republic of Lower Whingeing, the north and northeast by Hoblingland, on the west by the Solquist Sea, on the south by the tiny Principality of Gudrof, and on the east by the Lethean Sea.

History embroiders the UKIN's institutions and culture. Emerging from millennia of hard toil and centuries of struggle between ancient kingdoms and principalities that were the product of many human migrations, the United Kingdom as it is today is very much the result of gradual evolution rather than revolution.

Origins

The Emergence of Lethe

The Lethean Islands, as they are now known, form an archipelago situated approximately midway between Iceland to the north and Ireland to the south, having emerged from the North Atlantic as the product of a series of undersea volcanic eruptions and tectonic shifts.

The main island, Lethe, formed an essential bridge between Continental Europe, what became the British and Irish Isles, and the northern islands of Iceland and Greenland, serving as a way-station for many animal species. From the days of the Cambrian Explosion, when the warming submarine vents fed a wide variety of peculiar aquatic creatures to the amphibians, insects, soaring archosaurs, thundering dinosaurs, and eventually mammals of later eras that found their way to the islands, the Islands served as home to many animals, before the Ice Ages rendered the Lethean Islands uninhabitable save for a few species capable of adapting to the drastically colder climes.

The First Letheans

Early Settlement

The Lethean Islands, as they are now known, are a recent outpost of human habitation. Situated in the North Atlantic, this archipelago had been covered by an ice pack during the last great Ice Age. The earliest human fossil records found date back to around 6500 BC, long after the rest of Europe was awash with people. Those who arrived were modern, late-Mesolithic to early-Neolithic homo sapiens sapiens hunter-gatherers who appear to have relied upon fishing, whaling, and birds, as well as rudimentary agriculture for much of their diet.

Beyond those brief assumptions, garnered from animal bones and other evidence in and around a few well-preserved sites, and from ancient bodies found within peat bogs, little is known about these first inhabitants of what became Lethe. It is unknown what language they spoke, what sort of culture and society they possessed, and what beliefs they might have held. Fishing and kelp farming seems to have dominated the life of the early colonists. According to cave paintings as well as whale bones found near ancient coastal settlements, the inhabitants practised coastal whaling as well, using much the same techniques as practised by contemporary Anguistians until 1948. Land-based cultivation was reliant mostly upon hardy oat and barley grains that had accompanied the people from what became the British and Irish Isles and Continental Europe. These early groups practised animal husbandry as well, domesticating a local species of deer and the transporting in other domesticated animals from other parts of Europe over the centuries. Judging by these characteristics, the people were sophisticated albeit slightly behind their sub-Arctic and European contemporaries.

The inhabitants proved themselves adept at adapting to changes in their environment and material culture, perhaps in their society as well. In terms of working material, their culture changed little until approximately 1000-900 BC when the first evidence of bronze tools appears on the islands. The structures the people created, however, evolved greatly over those six millennia since their ancestors first stepped upon the shores, possibly as a result of new immigrants coming from the northwestern European islands (i.e., present-day Britain, Ireland, and adjacent islands).

Bronze and Iron Ages

The first written records regarding these early settlements came from Greek merchants looking for new sources of tin and copper after having been blown off course on their way to Ireland. They found the inhabitants to be distant cousins of the Picts of Scotland, speaking a broadly similar tongue, amidst whom they also found a few speakers of a mangled Irish dialect who appear to have been either merchants themselves or magnates. Polyphedos the Argive relates that the natives were "hospitable but untrustworthy, welcoming but xenophobic." There is no record of what the ancient Letheans thought of the Greeks.

Centuries later, another group came to the shores of presentday Isselmere. A Roman raiding party, sent by Agricola to reconnoitre Ireland came upon Lethe after being misdirected by a North Atlantic gale. Caius Paulinus seconds Polyphedos's analysis of native Letheans as a cultural offshoot of the Picts, including the propensity towards painting their bodies with what he assumed, incorrectly, was woad. Like their eastern cousins, the Letheans had no written language but did possess a highly stratified society. Paulinus notes that the Letheans were even more barbaric than the Caledonians, since the former captured and sacrificed one of the Roman soldiers to their gods.

In the period following the Roman departure from Britain and the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, Lethe became inundated by Briton refugees. The Iron Age Britons initially fared little better than the Romans against the Bronze Age Letheans, but over time the two cultures merged, with the invading new Brythonic languages being subsumed within the native Lethean tongue, which by then also possessed a fair number of words borrowed from Irish, Scots Gaelic, and even Basque. This new culture gave rise to the Anguistian language and culture, pockets of which may still be found in the northern principality of Anguist, one of the four component regions of the UKIN.

The Three Germanic Kingdoms

With the Roman presence in Britannia gone by the end of the fourth century AD, Romanised Britain (approximately present-day England and Wales) suffered depredation from Irish raiders in the West and from Germanic peoples in the East. Eventually, the latter groups, consisting of Angles, Saxons, Frisians, and Jutes driven from their homelands along the North Sea coastline by other Germanic tribes, invaded in force driving those Britons they failed to kill westward towards Wales and Cornwall and north to the Kingdom of Strathclyde.

In the process of consolidating their new lands, further groups were once again displaced and forced to seek their fortune elsewhere. Some of these groups ventured to Lethe in around the sixth century accompanied by a Roman Christian priest, Silvester of Lucca, later known as Saint Silvester of Lucca.[1] St Silvester reports in his History of Forgotten Lands that the native Letheans were no less barbaric than his companions/captors. The first group encountered, whom St Silvester called Picti based on the inhabitants similarities to their Scottish relations, purportedly believed that the Anglo-Frisians had come to trade and were quickly overwhelmed. Later tribes sought to use the Germanic invaders against their neighbours and similarly failed. Gradually, the Germanic peoples forced the Anguistians back to about the borders of what became Anguist and Nieland where they resolutely remained, occasionally sallying forth to wreak their revenge upon the invaders.

The process of retrenchment forced the Anguistians to regroup and reassess how they addressed the newcomers. Previously, each Anguistian king was owed fealty from a number of sub-kings, and he in turn might serve, however tenuously, a local high-king. With the loss of so much land and the constriction of the remaining populace to an area less than an eighth of what their predecessors held, the Anguistians were pressurised into finding novel solutions to responding to the Anglo-Frisian threat. In the end, they centralised authority. The same structure of high-king, kings, and sub-kings remained and kingship remained a personal rather than a strictly hereditary office, but authority had become direct. Anguistian notables caught treating with the Anglo-Frisians were dealt with brutally.

With co-operation came not only a strict hierarchy, but also the chance for glory and plunder. As the Anguistians drifted closer together, the Anglo-Frisians continued to squabble amongst themselves. Raids by the Anguistians finally forced the Germanic invaders to reply with their own more united kingdoms until there was an eventual stalemate between the large and comparatively well-organised Anguistian kingdom and the three Germanic kingdoms of Detmere, Isselmere, and Hoblingland.

The Detmerian kingdom was the first of the Anglo-Frisian kingdoms to arise in response to incursions from King Æderwald the Cunning of Wexsalia in southern Hoblingland, and steady pressure from the Anguistian king Urdath mab Mhaedoc, who retook what are now the provinces of Omechta and Upper Wingeria from the Anglo-Frisians. Friedwulf the Bald defeated his rivals at the Battle of Marsden Heath (14 April 842) to claim sole overlordship over Detmere before killing Æderwald at Hexford Row two weeks later.

The Kingdom of Isselmere emerged from the Battle for the Lethean Sea (24 October 863) when a fleet led by Hænulf of Isselmere, assisted by a large contingent from Anguist, vanquished a combined armada from Detmere and Hoblingland. Isselmerian independence was short-lived, however, as the Anguistian King Brudei defeated an Isselmerian host at the Battle of Solwent Moor (9 May 871) shortly after the death of Hænulf. Brudei's victory began a struggle for overlordship between Anguist, Detmere, and Isselmere, as well as Hoblingland on occasion, that often saw leaders contesting over the titular high-kingship of two, and, in four instances, three kingdoms (Anguist, Detmere, and Isselmere).

The Norse and Nieland

The Viking incursions of the ninth-century pressed the Anguistian and Anglo-Frisian tribal kingdoms into larger and more complex petty kingdoms. Initially, the Norse attacks were sporadic and unfocused. Over two centuries, however, the Viking leaders began colonising parts of Lethe, seizing lands to create their own kingdoms. The Hoblinglander petty kingdoms lost lands that became Wingeria, whilst their Isselmerian counterparts lost their southernmost lands in present-day Gudrof.

The Anguistians, however, were the hardest hit. Although, or maybe because, the Anguistians had been the pre-eminent force of the southern kingdoms, often driving the Hoblinglanders back to regain the high-kingship of the southern lands, they endured the worst of the Viking invasions. The Anguistian kingdom lost half of its territory to the Norse — present-day Nieland — and its dominance of the southern kingdoms. In the ensuing vaccuum, the Kingdom of Isselmere flourished.

The Rise of Isselmere

The Fall of Anguist

Isselmere's rise began with the after-dinner slaughter of the nobility of the neighbouring kingdom of Anguist by Forthar I the Brute on 19 May 985. Forthar and his co-conspirators, his brother Hengrist and the shaman Lormund the Foul, poisoned the mead of the visiting nobles simplifying the murder immensely. Forthar, after having killed his colleagues-in-crime, thereafter annexed Anguist and slowly imposed the Isselmerian culture upon the Anguistian. Despite this rather unfetching beginning, 19 May is celebrated as Coronation Day. Celebrants drink a mixture of lager and red wine to commemorate the event.

Forthar's dynasty, the Grœbling, was short-lived. His son, Gorm the Crude, married Ilse the Unready of Nieland on 12 January 999, and was subsequently murdered by her that night. Until the recent discovery of the Loundismund Annals, historians had assumed Ilse was simply unwilling to embrace her conjugal duties. It is now presumed Gorm's proclivities, which might have involved local sheep, could have been somewhat responsible. Forthar died in peculiar circumstances involving Ilse, Queen Maldren, and some local livestock on 15 February 999. Thus, the day after Valentine's Day is known locally as the Day of Happy Regrets (he died with a smile on his face).

Though it was unusual in those days for a woman to retain control over a kingdom, she cleverly managed to parlay her position as the former queen-consort to galvanise support behind her chosen candidates for the kingship — namely, two uncles and five cousins within the royal line — over whom she manifested immense control. As the power behind the throne, she was unparalleled and unquestioned. Eventually, she became the de facto monarch following the death of her youngest cousin on the distaff side, Forthar II (r. 1009-1011) on 21 November 1011.

The Christianisation of Isselmere and Anguist

Neither Forthar I the Brute nor Gorm the Crude were Christian in the modern sense. Forthar took to parlaying for the favours of local noblewomen and conducting the business of state during church services, occasionally drowning out the bishop, St. Joergen the Patient,[2] with his rambunctious laughter and, on one occasion, boisterous love-making emanating from his balcony pew. On those rare occasions Gorm went to church, he stumbled in mid-sermon, uttered loud profanities while finding the family pew, before passing out from the previous night's exertions. Queen Maldren, brighter than both her husband and son, used the Church to further the consolidation of power within the monarchy, insofar as was then possible. Ilse, despite the bloody annulment of her marriage with Gorm and the death of Forthar, remained in Isselmere to become the Abbess of St. Silvester-on-the-Hill at Torchtshill, modern-day Tortshill.[3] Maldren and Ilse combined to Christianise the nobility by moral suasion, royal favour, and force of arms with some success until the death of Queen-Dowager in 1013.

The marriage of Maldren and Forthar produced two daughters and one son that survived into adulthood. Gorm died leaving two young illegitimate sons but no direct heir, and no woman willing to admit they had sex with him. The eldest daughter, Cloda, had married King Karl the Dim of Detmere but had produced no male heir, for which Isselmere was thankful. The other daughter, Jogalla the Sane, had wed Bengst the Stout of Gudrof. Two local magnates, Unguin the Bold and Stortbek the Bitter, also vied for the throne. Thus, the Isselmerian nobility faced four pretenders to the high-kingship of Isselmere and Anguist. The nobles met at Pechtas Castle in Daurmont to make their selection as the pretenders waged war against one another in running battles through-out the kingdom. Eventually, the Abbess of St. Silvester and Bishop Joergen brokered a peace deal between the two remaining pretenders, Bengst and Stortbek involving a trial by combat for the kingship.

King Bengst I the Stout of Gudrof and Earl Stortbek the Bitter of Glaines met on Tiw's Plain on the outskirts of Daurmont before the assembled magnates of Isselmere-Anguist. Bengst, owing to his wife's good offices, was a convert to the new faith while Stortbek, who celebrated the morning by sacrificing his favourite ox, was a staunch traditionalist. Neither contender had many supporters among the attending nobles. The Christian nobility worried about losing the sovereignty over their fiefs to a foreign king who might prefer his own nobles to the locals, as well as concerned about the possibility Bengst would use the Church to undermine their independence, while Stortbek was fighting a hopeless battle to retain the old religion, as well as being temperamentally unsuited for a position requiring sound judgment and diplomatic acumen. Fortunately for the nobility, both men were an able match for one another: after twenty minutes of raining a flurry of blows each other and retiring, Stortbek struck Bengst a fatal sword blow to the chest just before Bengst cleft Stortbek's head in twain. As both men lay dying on the field of combat, the council of nobles elected Bishop Joergen as their king, much to his dissatisfaction.

St. Joergen the Patient was the scion of a noble family, but was honestly pious. He had spent twenty of his thirty-nine years proselytizing the hinterlands before returning to Daurmont in ill-health. He also had no interest in either marriage or concubinage. To the council of nobles, he was eminently suitable. He had, however, one seemingly cruel condition before being browbeaten into acceptance: should the pregnant Cloda produce a male heir, the child would be king of Isselmere, Anguist, and Detmere. In spite of their outrage at that demand, the council entrusted the throne to Joergen. Cloda did indeed have a son, Joergen II, and Joergen I educated the boy in the ways of the Church and Isselmere before dying at the ripe age of sixty-four, having outlived most of the councillors who had elected him.

In the quarter-century between his accession to the throne and his death, Joergen I consolidated the position of the throne in the politics of the three kingdoms and, through his wise leadership, advanced Isselmerian culture within the larger settlements. In these tasks, he was aided by the indifference of the Vikings who, upon seeing the small kingdom's shores, left for what they believed were more prosperous lands. The Church benefitted greatly from the stability and support Joergen gave, and established several monasteries and churches to secure the faith in the fabric of daily life.

Joergen II the Good continued the good works of his predecessor both in governance and the Church. He arbitrated the frequent squabbles between the nobility, and between the nobility and the commons with great wisdom. In 1039, Joergen II ensured his hold on the conjoined kingdoms by marrying his second cousin, Lotte of Huis. With the birth of their son, Ætheling,[4] the Joergenian dynasty was secured.

The Joergenian Dynasty and the Black Death

King Ætheling (r. 1063-1085) knew he was not as able as his predecessors, so he tried to steer his course based on the advice of the court. Unfortunately, the magnates both temporal and spiritual were argumentative and directionless navigators of the ship of state. The beginning of conciliar power was frought with internecine strife. Merely two months after his coronation on the stone seat of Isling, a meeting of the peers degenerated into a war when Odthar Græbek, Bishop of Semling, killed Hrust the Impudent Froeling, Earl of Bormunst, with his crosier during an off-topic debate on the nature of the Trinity. Ætheling's attempts to arbitrate came to nought as four armies ravaged the countryside: the Froelings, the Græbeks, an army of disgruntled serfs, and Nielander mercenaries hired by the king. After two seasons of warfare, the Froeling of Bormunst and the Græbek of Semling agreed to settle the matter, symbolically exchanging pigs for sheep, allowing the magnates and the king to combine against the peasants.

The peace the king brokered between those two great families might have led to royal dominance over the magnates. Royal debts incurred by the War of the Crosier and the dowries for his six daughters forced the king to demand further funds from the nobles. The nobility, which was already using brutal means to extract the most profit from this method of tax-farming, refused to pay the king's present and future debts unless he and his successors secured the advice and consent of the council of peers. Even so, the money obtained from that promise was insufficient, necessitating in the sale of royal offices. The Keeper of the King’s Privy, Althust Oetting, Earl of Cuidmur, and the Keeper of the Bedlinen, Toerst Nieling, Baron of Rœthæbn, led a court rebellion against the sales. Learning that the king was replacing the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Ardath Caitwuil, Baron of Glaines, with a greedy but paying rival, Paerbor Felsing, Baron of Sluist (Detmere), Cuidmur and Rœthæbn gathered the court nobles in a conspiracy to undermine the throne. As Keeper of the King’s Privy, Cuidmur was responsible for safeguarding the king’s health. One day, Cuidmur proclaimed the royal stool to be a little off-colour and foul. Ætheling, examining the matter himself, demanded a second opinion. The Keeper of the Bedlinen concurred with the King’s Privy, leading the now outraged Ætheling to clout the two nobles with his chamberpot. The King then called in Queen Jehanne of Caen for her opinion. Jehanne, a co-conspirator, agreed with Cuidmur and Rœthæbn, upon which the Ætheling crowned her with the chamberpot. In the ensuing royal battle, Ætheling lost two teeth and the sight in his left eye, and Jehanne was left without part of her right ear and with a limping left leg. Unfortunately for the rebellious nobles, this brawling foreplay not only convinced the royal couple to cooperate to demand greater funds, but also led to a royal heir, Berthuis I (r. 1085-1097), greedier than any of them.

Berthuis I the Ravager ensured that the kingdom was no longer in debt but in a constant state of unrest. Peasant revolts were frequent, leading to many attempts on the king's life within the Court of St. Silvester. Even so, when Pope Urban II declared the First Crusade in 1095, the nobility in collusion with the commons and the peasants were able to scrape enough together to send their avaricious monarch. He died in Antioch in October 1097 at the hands of his fellow crusaders.

With the king away slaughtering infidel, the council of peers nominated Loþcærl Muilsen,[5] Earl of Woulten, as regent for eight-year-old Berthuis II (r. 1097-1132). Woulten was a degenerate, but thrifty. Under the supervision of the Queen, Ulla of Hobling, the young Berthuis only adopted the latter trait. The country benefitted greatly from the Crusades as the near constant infighting between the peers became occasional swordfights in the court itself: the labour shortage in mercenaries made sieges too expensive. Woulten and the Queen were still able to use this infighting between nobles to secure the support of the increasingly wealthy commons.

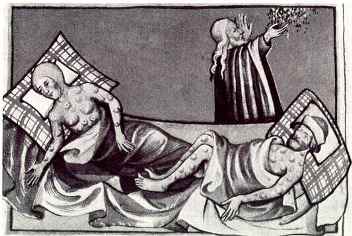

Over the generations between Berthuis II and Guilherm III (r. 1343-1349), each group — royals, nobles, and commons — learned to exploit the weaknesses of one another granting the three kingdoms of Isselmere, Anguist, and Detmere the stability to coalesce into a reasonable fascimile of a nation, albeit with three different traditions of common law. The arrival of the Black Death in 1348 hastened the process by killing off up to forty percent of the villagers and townspeople, twenty-five percent of the peasants, and thirty percent of the nobility including the last members of the Joergenian dynasty. Escaping from the putrid Heringhof Castle to the outskirts of Daurmont, the remaining peers and commons, elected Normain Houmbertis, Duke of Glaines, as King Alfred I (r. 1349-1372). The former duke never explained why he chose the reign-name Alfred instead of Norman, though courtiers often wondered why the name caused the king to look wistful.

The House of Glaines

Reconstruction

The Black Death, while devastating, offered peasants and villeins greater opportunities. In the years preceding the plague, population increases threatened famine and undermined wages and the standard of living for many in the lower orders. With the competition for food and work far less severe than before the outbreak, peasants and labourers benefitted greatly. Those surviving peasants fortunate enough to have converted their payments for rents and other obligations from those in kind to fixed money amounts profited at the expense of the nobility. Other peasants tried to do the same with some success initially as the nobility and gentry attempted to keep their serfs on the land rather than securing work in the towns. By October 1349, however, the plight of the landholders became so desperate that they pleaded with Alfred I (r. 1349-1372) for a law to reverse the unwelcome social mobility. On 4 November 1349, the king proclaimed the Tenancy Act that fixed wages and dues for labourers and peasants at pre-plague levels, including retroactively reassessing agreements made before the act, and forcing all peasants who moved to the towns before August 1349 back to the land.

The resulting revolt, led by Ulf Toel, forced its way to Daurmont's walls before being reversed by the townspeople — mostly through bribes and information regarding the location of the king and council — who were suffering street battles of their own. A major battle between about 2,000 peasants and labourers and an aristocratic army of about 150 knights and nobles and approximately 600 retainers led to the retreat of the latter force with the loss of 27 knights and nobles and a couple hundred retainers. The peasants and labourers lost almost half their number, but Toel pressed them onward and secured more followers along the way. At Stoughton Bridge, Toel and Alfred I met on the field of battle. This time, a disciplined horse charge routed the rebellion. Toel was captured and given exemplary punishment before the remaining rebels, of whom only twelve were permitted to live to tell of their failure. The aristocracy then turned its attention towards the towns. With the aid of the burgesses, the nobility and gentry quelled the urban revolt by 12 December 1349. The day is commemorated by employees of all stripes as Toel's Day: all work to rule (or the Friday before if it falls on the Saturday, and Monday if on the Sunday) and the Act is burned in effigy in drunken bonfires.

The House of Glaines battled to maintain stability within the kingdom over the next two centuries. Internecine warfare, which had troubled the reign of Guilherm III as the pre-plague populations rose and as land and resources came harder to find, threatened to topple the new dynasty as the nobility and gentry scrambled to secure the lands and titles of defunct lineages. Luckily, the burgesses of the commons, despite threats from various quarters, refused to grant 'gifts' to supply aristocratic armies, thus allying themselves with the king. Correspondingly, in 1351 Alfred I removed six towns and their environs from existing noble fiefs and created six new counties. The nobility were too militarily and financially exhausted to complain. Alfred I, after browbeating his magnates, established a Court of Rolls (1352) to handle land and inheritance disputes. The establishment of the court unleashed a small army of surveyors and tax assessors on the kingdom leading to the The Rolls of Grand Manses. The Grand Roll, as it is more commonly known, became the basis not only of tax assessments — head tax, essential commodity taxes, land tax, etc. — but also served, unintentionally, to formalize membership within the Council of Peers and the Royal Assembly of Burgesses, thus is one of the founding documents of the present-day Parliament.

The creation of a labour shortage by the plague invigorated efforts to invent or import labour-saving devices and practices. Urbanization and the stepping stones, admittedly far removed, to industrialization began in these times under the very watchful eyes of the merchant and craft guilds. Education was also broadened, at least among the propertied classes. Alfred I founded the University of Daurmont under royal charter in 1361, followed by two other universities established under Church auspices in 1363 and 1364.

The Union of Isselmere and Nieland

Increased wealth brought an increased lust for territory. From Guilherm I (r. 1257-1284) to Guilherm III (d. 1349), Isselmere engaged in a series of wars against the neighbouring kingdom of Nieland. Isselmerian kings claimed the Nielander crown as theirs by right of marriage (between Gorm the Crude and Ilse the Unready in 999, though it was unconsummated). The Nielanders resisted ably along the River Salny and the Quismond Mountains and, despite two short periods under Isselmerian rule (1276-1284 and 1343-1349), they remained independent. Alexander I (r. 1401-1427), using the same excuse as before, began the effort against Nieland again. By 1513, both kingdoms were spent and envoys were sent. On 25 June 1513, Princess Hortense of Isselmere, eldest daughter of Alfred V, married Crown Prince Maximilian of Nieland, son of Eðalbjart II. Little did either king know that this marriage would cement the two lands together in perpetuity.

What would later be celebrated as Union Day (25 June) was not then considered an event of monumental importance. Both Alfred V of Isselmere and Eðalbjart II of Nieland believed the marriage of their offspring was just an extended respite from the continuing brawl between the two kingdoms. Hortense of Isselmere and Maximilian of Nieland were both young — fifteen and sixteen years old, respectively — and their fathers were both hale and hearty. Within ten years, the three men would be dead and Hortense the queen of an expanded united kingdom.

At the time of the marriage, Eðalbjart (a.k.a. Albrecht or Albert) was an adventurous monarch of thirty-four years in the sixteenth year of his reign who enjoyed a good joust as well as heavy meals. In 1518, he decided to enter a friendly contest — entirely against convention — with one of his favourites, the Lord Constable the Duke of Slyddhöfn. Eðalbjart, who was suffering the early stage of another bout of gout, met his opponent on Wotan Plain just outside the capital, Felsingborg. Owing to the pain he was suffering from his gouty leg, Eðalbjart could not concentrate fully on the joust. Slyddhöfn unhorsed the king on the second pass, breaking Eðalbjart’s diseased leg. Despite the great pain he suffered, the king awarded Slyddhöfn for his success by naming the duke Lord of the Northern Marches. The office was suitably distant from Felsingborg. Eðalbjart’s fate was dimmer. The king’s broken leg soon led to septicemia and death. On 29 August 1518, a week after his father’s fall, Maximilian was crowned king.

Alfred survived another five years before succumbing. After the departure of his favourite, Hortense, to Felsingborg, the king of Isselmere became paranoid. Alfred suspected the crown prince, Edmund of Glaines, of conspiring with his two other sons, Richard of Detmere and Henry of Daurmont. The monarch sent the three away to neighbouring lands hoping for them to die by piracy, banditry, disease, or debauchery. Within two weeks, his most trusted servant, Rudiger, Earl of Overlea and Lord Steward of the King’s Bedchamber, poisoned Alfred in a bid to steal the throne. The earls of Grayling and of Tortshill, respectively the Lord Privy Seal and the Lord President of the King’s Privy Council, captured the traitor and recalled the princes immediately. Henry, however, had died in a drunken brawl in Hoblingland and Richard was suffering from tertiary syphilis in Wingeria, present-day Lower Whingeing. Edmund returned immediately from England and was crowned on 27 June 1523. Regrettably, another serious outbreak of plague hit that year, claiming young King Edmund and much of his court before they were able to flee the capital.

Thus did Hortense become Queen Hortense of Isselmere, as well as Queen-Consort of Nieland, on 18 September 1523. Hortense, though six months pregnant, travelled alone to her coronation as King Maximilian was fighting off a Wingerian incursion. As her recently uncovered diaries indicate, the young queen was thankful her husband was not there. She rightly feared that the Isselmerian Privy Council and Parliament, which worried that Maximilian would assume control over both thrones, would rally to the cause of one of the two other pretenders, Hortense’s uncles George, Duke of Huise, and Edward, Duke of Angforth. Upon her arrival at Pechtas Castle, the revelation of her pregnancy nearly caused a revolt within the Parliament. Furthermore, the Archbishop of Daurmont was concerned that a woman in such a late stage of pregnancy might not be sufficiently godly to accept the crown. Once the Lord President of the Privy Council changed the Archbishop’s mind a dagger-point, and the speakers of the Peers and the Assembly threatened to assess additional levies from dissenting members, the coronation ceremony was underway. In the end, the Isselmerian élite had no cause to worry. Maximilian managed to get himself killed in a foolish charge against the Wingerians on the morning of 16 September 1523, the day after Hortense had left Felsingborg.

Hortense I the Bald (r. 1523-1552) had planned to remain in Daurmont until giving birth. News of Maximilian's death, however, sent her back to Felsingborg. Three other claimants to the Nielander throne threatened her status as queen and the security of Nieland. The first pretender was Maximilian's uncle, Edvard, Duke of Aldmark, who behaved as if the throne held no interest for him but whose supporters were extremely powerful and vehement he ought to be king. The second was Peder, Earl of Guðhilfborg, was Maximilian's bastard half-brother. He was neither particularly clever nor well-supported, but he was quite vociferous in declaring his intention to grab the crown by any means possible. He was, fortunately, killed by the third candidate, Óláf, Earl of Työþingi (Isselmerian Twerting). Twerting was a nasty brute and was adequately supported. Thus, when Hortense arrived at the Nielander capital, the small kingdom was already in the midst of an overt dynastic struggle. Hortense tried to broker some sort of peace between the two pretenders but neither recognized her own claim to the throne. Eventually, Aldmark defeated Twerting at the Battle of Erlsford Bridge (24 February 1524).

A difficult problem arose. Had Hortense given birth to a son, the Nielander parliament — the Storting — would have made her and Oltmark co-regents. Hortense's daughter, Beatrice Hortense, had no such guarantees. Another war loomed until Aldmark, a vigorous and libidinous man, died mysteriously in the bed of one of his mistresses. Aldmark's supporters thereafter fell against one another, leading to battles within the court and on the streets of Felsingborg. Finally, the uncommitted members of the Storting and the queen's supporters rallied against their less numerous but more combative fellows to proclaim Hortense as sovereign in her own right, but only so long as she not remarry. Hortense, content enough to play the field, accepted and was crowned on 16 April 1524.

Hortense had long found life in Felsingborg dull, so left the Nielander capital to Frederick (Nielandic Friðarík), Aldmark's son, as lord high commissioner (i.e. viceroy), and returned to Daurmont. Her reign was successful insofar as it was generally uneventful, with the exception of a few border troubles, and left much of the more boring tasks to Parliament and the Storting. The only real excitement before 1549 was the event that gave poor Hortense her epithet. In 1532 while Hortense was inspecting the Isselmerian flagship, the Royal Holly, a cannon charge exploded prematurely, killing sixteen sailors and burning off Her Majesty's eyebrows and much of her hair. Thankfully, it was already the custom to wear wigs at court but the accident still ruined her extra-curricular activities.

The development of strident Protestantism in 1549, however, disrupted the calm within the two kingdoms. Hortense had left the quieter Protestants alone for the most part, but when Zwinglians escaping from Central Europe arrived on the shores, she begged the Pope to establish a local inquisition. The Isselmerian and Nielander inquisition was not particularly brutal, but the secular suppression of unrest was. After that first episode, leading to a peasants' revolt in 1551, the crown considered even the arrival of the less revolutionary Lutherans in January 1552 as a threat to the public order. Despite Hortense's aversion to the Lutherans, the Storting, led by Frederick, allowed the sect to root itself into Nielander society.

With the death of Hortense I in May in another plague epidemic, Hortense II the Cunning (r. 1552-1589) permitted the establishment of a Protestant Church throughout her kingdoms. The newly Protestant state obliged Catholics through punitive measures to convert, but engaged in no confiscations or arrests for private acts of faith. Catholics were, however, prevented from public displays of faith. Threats to cathedrals and religious artefacts--sparked by Protestant iconoclasm--led Hortense II to impose harsh measures against offending Protestants. Catholic cathedrals became royal property, guarded by royal soldiers. Indeed, the first standing regiment, the Royal Temple Guards, dates from this period.

Hortense II eventually married, Henry, Duke of Aldmark, in 1557 in response to pressure from both the Storting and Parliament. Recent research indicates that Hortense prefered the company of other women, as did Henry, but the two were able to produce two sons and a daughter, all of whom lived to adulthood.

The marriage between Hortense and Henry also consummated the union between Nieland and Isselmere. On 25 June 1562, the Storting voted itself out of existence and its members moved to take their seats in the united Parliament.

Around this time, the Renaissance was finally flourishing in Isselmere and Nieland. No greats of the stature of Michelangelo, Niccolò Machiavelli, Christine de Pisan, Albrecht Dürer, or William Shakespeare were produced, but lesser geniuses adequately served to further the kingdoms' social and cultural development.

Religion, Toleration, and the Royal State

Sectarianism wracked the period between the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Old Believers — those few Zwinglians who escaped both the Isselmerian Inquisition under Hortense I and the Lutheran Conversion under Hortense II — continued to generate peasant unrest wherever they could. The Lutherans, meanwhile, were struggling with the arrival of Calvinist theology from Scottish Presbyterians and French Huguenots. Battles raged in Protestant churches over the Eucharist, causing the Church of Isselmere to split into the Conventionalists (the Lutherans) and the Symbolists (the Calvinists). King Robert I (r. 1589-1612) supported the Conventionalists on the basis of consubstantiation (i.e., that the body and blood of the Son co-existed with the bread and wine). King Harold (r. 1612-1618), attempted a return to the Old Church (i.e., Roman Catholicism), but the eruption of the Thirty Years War and his general unpopularity led to his assassination at the hands of a disgruntled servant. Robert II (r. 1618-1651), buffered by monetary and literary support from a burgeoning emigré Huguenot community and desperate to avoid direct involvement in the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), supported the Calvinists. Edmund II (r. 1651-1684) avoided making any decisions on religion after witnessing the troubles in nearby Scotland and England. His excessive caution allied with his marriage to Sólveig of Gudrof in 1653 and the concomitant growth in the number of his Lutheran subjects allowed the brief but vicious Civil War to erupt (1684).

The Civil War was not a battle betwixt Crown and Parliament, but a sectarian brawl au large. Conventionalists fought Symbolists, and Zwinglians and Catholics fought with and against both and each other. What eventually emerged was the Act of Toleration, 1684, an event relived with each State Opening of Parliament. The two Houses meeting in joint session in the Hall of Congregation engage in a mock battle. The monarch, protected by a small retenue of four guards, advances towards the Clerk's Table, snatches the Mace of the Senate (formerly of the Peers), and proclaims loudly "We command thee desist or we shall brain the lot." Government and Opposition leaders then are compelled to shake hands and take their seats, while backbenchers clean the mess. Historically, however, the event had a more violent end: the leading representatives of the factions advanced on King Edmund, who with one swipe, did exactly as he said he would. This exertion triggered a fatal heart attack, but the Act of Toleration was duly enforced by Edmund's son, Alexander II.

The Act established the Reformed Church of Isselmere (Calvinist) as the State religion, supported and defended by the monarch and governed by a General Assembly. The Lutheran Church of Isselmere became simply the Church of Isselmere and was granted the right to retain its churches, but was not permitted to build new ones without royal charter until 1723. The Roman Catholic Church was granted royal protection from iconoclasts, was not permitted to build new churches without royal charter until 1789, its followers were subject to some civil restrictions (e.g. could not receive royal offices), but otherwise it could worship freely. The Zwinglians, as usual, were ignored.

Alexander II's long reign (r. 1684-1723) assured the success of the Act of Toleration and granted Isselmerian society time enough to prosper. The king used his newfound authority to centralise power. His first measure was to unite the Isselmerian and Nielander legal traditions by abolishing the courts of the lords and gentry and establishing royal courts of process and appointing royal magistrates throughout his realms (1692). The lords and gentry thus lost the control over lesser civil and criminal violations they had abused for centuries. The Council of Peers loudly condemned the measure, but they balked against a potential war with the king and the burgesses. Instead, a majority of lords, and a minority of the gentry in the House of Assembly, refused to perform their legislative duties, and all judicial proceedings in the Peers stalled. The king, in collusion with the Assembly, circumvented the Peers and instituted the Royal Court of Justice to administer justice over the entire United Kingdom (1697). Finally, the Peers acquiesced in Alexander's royal revolution and were regranted ultimate appellate jurisdiction over the nobility.

Notes

|

| Topics on Isselmere-Nieland | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | Factbook Categories: Administrative divisions | Constitution | Defence Forces | Festivities | Government | Languages | Laws | ||