Lethe (region)

Lethe, or more correctly, the Lethean Islands, is an archipelago situated north-northwest of Ireland and south-southeast of Iceland. The Solquist Sea separates the region from Iceland, whilst the Tichonian, Lethean, or Eastern Irish Sea divides it from Ireland.

The island chain is home to five countries. Clockwise from the north, these are Azbinia, which spans the entire northern third, Hoblingland, occupying the eastern middle third, Isselmere-Nieland that dominates the southern third with shores on both of the main island's coasts, Gudrof to the very south, and Wingeria in the western middle third.

Contents

Etymology

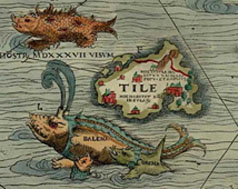

The archipelago has had several names over the past few millennia. The ancient Greeks who traded with the Islands' inhabitants for tin and copper called the land Θούλη or Thule as well as the Forgotten Islands (Λήθη νησοί). The Romans who escaped their first and last visit to the Islands called them simply Ithlis, a word derived from Lethe, as well as Lethe for a land best forgotten. The modern Anguistian term for the island chain is Enais Lethnógha or the Twilight Islands. Both Thule and Lethe, and various spellings thereof, were used by early writers to refer to the Islands, with the latter term winning by the middle of the 19th century, mostly due to the rise of James Macpherson's Ossian poems and the brief resurgence of the native Celtic language southern third of the main island, known then as the United Kingdom of South Lethe.

Thule passed into the annals of history, at least among polite circles, throughout the archipelago with the rise to power of National Socialism in Germany in 1933. Consequently, Thule is still used by some far-right parties, particularly in Gudrof, Isselmere-Nieland, and Hoblingland.

Prehistory

Origins

The Lethean Islands, as they are now known, emerged from the North Atlantic as the product of a series of undersea volcanic eruptions and tectonic shifts. The main island, Lethe, formed a bridge between Continental Europe, including what became the British and Irish Isles, and the northern islands of Iceland and Greenland, serving as a way-station for many animal species. From the days of the Cambrian Explosion, when the scalding submarine vents fed a wide variety of peculiar aquatic creatures to the amphibians, insects, reptiles, and eventually mammals of later eras, the Islands hosted many lifeforms until the Ice Ages rendered the region almost uninhabitable.

The first Letheans

Hominids came late to the Islands, arriving in the second millennium BC by which time the ice had finally receded. These first settlers were modern, late-Mesolithic to early-Neolithic homo sapiens sapiens hunter-gatherers who relied upon harvesting kelp and seaweed, fishing, whaling, and seabirds as well as rudimentary agriculture for much of their diet.

Beyond this brief information, garnered from animal bones and other material evidence in and around a few well-preserved sites and from ancient bodies found within peat bogs, little is known about these first colonists. Whence these settlers came is still a matter of conjecture, although based on the existing fossil and material record, the Islands appear to have been colonised by Western Eurasians, possibly from northern Scotland. By 1800 BC, the settlers had established themselves throughout the archipelago comprised of coastal settlements of sandstone built into and atop of middens, as well as some within existing hills, as at Skara Brae and Knap of Howar, evincing maritime linkages with what became northern Scotland.

Unlike the dwellers at Skara Brae, the early inhabitants of the Islands did not abandon such dwellings until around 1500 BC despite the steadily worsening climate. Unlike the inhabitants of Skara Brae, the ancient Letheans had nowhere more salubrious to go, with sturdy pines and fir trees deep inland hampering agricultural development and the great difficulty of catching and, in the case of the barley-tail deer, domesticating the few native animals on the Islands, especially considering the relative abundance of aquatic food sources, notably whales, seals, and kelp.

These coastal dwellings appear to be closely associated with intricate chambered cairns, which emerged at a much later date in the Lethean Islands than in the rest of Europe, as well as more elaborate cairns and eventually intricately carved stelae, the latter originating in around 900 BC. The stelae represent animals such as the barley-tail deer — which had been domesticated by that date — the Apphelian ibex, the Atlantic salmon, the silver trout, and the polar bear, as well as peculiar man-animal hybrids that might be deities or spirits of the hunt.

In around 2200 BC, the ancient inhabitants of the Lethean Islands began establishing crannogs, particularly in the southern lakelands in what is now Gudrof and southern Isselmere and Nieland, whilst in the more northerly areas the precursors of Bronze Age brochs of stone and wood emerged rising to the height of 3m, at first near the earlier excavated dwellings but then ever deeper inland. The earliest of these broch-like structures have been radiocarbon dated to around 1500 BC, just after the arrival of the Bronze Age, with older, less impressive semi-excavated stone structures sited nearby.

Bronze Age

Based upon the archaeological finds in stannaries and copper mines throughout what is now Lethe, the Bronze Age appears to have arrived in the Islands about 1400 BC, approximately four centuries behind the peoples inhabiting the present-day British and Irish Isles, and ending about 500 BC with the commencement of the Iron Age.

Widespread deforestation marked the Lethean Bronze Age, as did the manufacture of sea-going vessels capable of trading with Europe constructed from the resulting lumber and the building of impressive brochs, the remnants of which can be witnessed in present-day Anguist.

Researchers presume that ancient Letheans had received broch-building techniques from the Hebrides, but recently Úruist mab Tállogh and Owen Cartwright of the University of Mithesburgh contested this established notion. Mab Tállogh and Cartwright postulate that the Lethean brochs were developments of the earlier coastal dwellings based upon the similarity of construction techniques and the continuation of the practice of building upon excavated earth or midden mounds.

It was previously assumed that the underground floor served to shelter less hardy livestock during the long winters before the arrival of hardy Icelandic sheep and Highland cattle circa 700 BC. Recent archaeological studies have disproved that theory. Until the influx of the hardy cattle and sheep, the barley-tail deer — and dogs — were the sole domesticated animals, the former requiring no shelter from their native habitat. This situation meant that a mixture of fixed and nomadic transhumance was common among most ancient Letheans. Only after the appearance of domesticated pigs circa 100 AD were the ground floor of Lethean dwellings used to shelter livestock in winter.[1]

Historical Lethe

References

- ^ Domesticated pigs, unlike Lethean boars, had short-hair that provided minimal protection from the harsh frost and bone-chilling winds.

| Topics on Isselmere-Nieland | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | Factbook Categories: Administrative divisions | Constitution | Defence Forces | Festivities | Government | Languages | Laws | ||